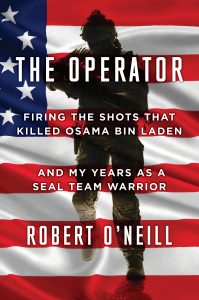

My recent ghostwriting project, The Operator: Firing the Shots That Killed bin Laden and My Years As a SEAL Team Warrior, published today, April 25, and as of noon it was #4 on Amazon bestsellers list. Robert O’Neill is a smart, articulate guy with a one-of-a-kind story to tell. You can read the first chapter here, just click on “Look Inside”. Check it out.

My recent ghostwriting project, The Operator: Firing the Shots That Killed bin Laden and My Years As a SEAL Team Warrior, published today, April 25, and as of noon it was #4 on Amazon bestsellers list. Robert O’Neill is a smart, articulate guy with a one-of-a-kind story to tell. You can read the first chapter here, just click on “Look Inside”. Check it out.