Man, if this doesn’t show the magical tendency of a non-fiction narrative to resolve itself in spectacular, wilder-than-fiction ways: Consider the story of the decline of long-form journalism, then read this account of its final days in the newsroom of one of the former lead practitioners of the form. Pay particular attention to the closing paragraphs.

Author & Editor

Blog

The Final Rounds

The Surreal Housewives

Hank Stuever was a brilliant chronicler of social culture — the deadend shopping strip mall, the man who cleaned up roadkill deer carcasses, the cult of the white plastic chair — but could he bring the same insouciant clarvoyance (in the strict sense of clear sight) to TV coverage. Well, bien sur. Check out his wonderful critique of the new Real Housewives of Orange County season. It practically shimmies and shakes off the computer screen: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/10/29/AR2009102905242.html?sub=AR

You have to read it all. Every paragraph — every one — has it’s delights and revelations, it’s word play and sly subext. But here’s a favorite:

“This is Bravo doing what Bravo does best — imparting, in the slyest and most intuitive of ways, a sense of what’s right and what’s wrong. Much hubris (and many martini happy hours) brought us collectively to this point and now a new reality pervades the lifestyles that Bravo built its schedule exalting; the Great Recession has given its schedule more texture and human foible, and, in a way, it feels like the people at Bravo knew this would happen all along and set us on a path of social justice.”

There Are No Bad Stories

My Q-A with the Nieman Foundation Story Board by Andrea Pitzer:

Tom Shroder, former Washington Post Magazine editor, on dinner plates and well-done narrative

This week, I had a chance to talk by phone with Tom Shroder, who took a buyout from The Washington Post earlier this year. Shroder specializes in long-form narrative stories and recently launched his own editing site. While I did minor freelance work for the Magazine during Shroder’s tenure, I had never talked with or been edited by him, so I was curious what he would have to say about the current state of narrative journalism. In our conversation, he dishes on a common mistake made by narrative freelancers, talks about the genesis of one of the best newspaper narratives ever written, and a offers up a considered defense of poop jokes.

Tell me a little about your background and what you’re doing now.

I’ve been an editor of a Sunday magazine—first for The Miami Herald and then The Washington Post—since 1985. And I’ve been editor of the Post Magazine for the past seven years. I just took the buyout, and I’ve now founded a website called StorySurgeons.com.

You’ve no doubt read a lot of submissions from experienced and beginner long-form reporters. When stories don’t quite work, is there a common point at which they fail?

There are a million places a story can fail, from the initial conceptualization all the way through to the final execution. I think that the most important thing is for someone to understand what the story actually is and the nature of a story. I think that most people, especially inexperienced people, who send stuff—they’ll have no idea what a publication actually does. It’s amazing how many submissions we got that had no relation to the kind of work that ended up in our pages.

Is there a template you have in your head for how you approach editing narrative work? What usually comes first, and what comes last?

What you want is to very quickly understand why there might be some promise in investing time in this thing. You want something to engage your attention. Usually that involves conflict or something unexpected, even just tension between ideas and characters in the scene itself.

Recently on Nieman Storyboard, Tom Hallman of The Oregonian said that there will be problems in newsrooms whenever editors divide staff into two camps, the writers, who are coddled, and the reporters, who work the night shift. Do you find good reporters to be a separate group from good writers?

I’ve never believed that good writing exists independently of what you are saying in your writing. What makes good writing is tremendous understanding of a subject and attention to detail. What good reporters do is dig up incredibly powerful and meaningful detail.

Not all reporters know how to tell a story very well, but you can help them with that as an editor. You can help a good reporter to tell a good story. What you can’t do is tell a good story if you don’t have the facts lined up behind it—in nonfiction, at least.

Where a lot of narrative journalism went wrong was that it became all about the writing, and not about the details for the story and the facts behind it. People felt they could throw some words at people and dazzle. But even good writers need to start with an exceptional set of facts.

You’ve edited a lot of newspaper humor, from Dave Barry to Tony Kornheiser. Is there anything fundamentally different between your approach to editing humor stories and long-form narratives?

The humor things are usually much shorter to begin with, but I approach all editing the same way. I look at something and demand to be engaged from the first word to the last. I have no tolerance for being bored. I read through things and take note of where my attention is being lost. In humor, it’s because the joke isn’t working, either because it doesn’t scan logically, the idea is flawed, or it’s too expected, too clichéd.

I’m thinking of Gene Weingarten, whose best stories seem mash up comedy and tragedy. The Battle Mountain piece that ran not long after the 9-11 attacks, in which he tried to find the armpit of America. And the profile of the great Zucchini, a children’s entertainer with a very complex personal history. Is there a secret to making that comic-tragic mix work?

The secret is a deep understanding of where humor comes from. Humor comes out of our very vulnerable and frightening position in a huge and uncaring universe. What humor does is turn the table on our fear. By laughing at it, we make ourselves feel better about it. We’re all made so we desperately want to live forever, but we’re all going to die. If you step out yourself a little, you can see how ridiculous it is.

Gene is very aware of the absurdity of an individual’s position in life, and he uses it to create humor at the same time that he’s putting together really moving material, and—

And poop jokes. Weingarten seems to like those a lot.

Absolutely, if you think about why poop is funny. Here we are. We’re all going to die. And in order to make ourselves feel better about it, we pretend that we are these pristine vessels. Yet every day we wake up, the first thing we do is emit this bolus of decay.

Poop and mortality are metaphors for each other. That’s why poop is funny. The absurdity of our condition is that we walk around with this absolute conviction that we’ll live forever. Poop jokes are a way of reminding you in an irreverent manner that you’re mortal. So even the poop joke has a serious role to play in telling a story.

How have newspaper narratives changed in the three decades you’ve written and edited them?

Back when I started at the college newspaper in the 70s, that was the heyday of what was then “new journalism,” though of course, the new journalism really wasn’t new. Narrative was not an invention of the print media. Which is good news, because as print media is struggling and contracting, people think that it could mean the death of narrative journalism as we’ve known it. I don’t think that’s true.

Narrative is the way that human beings are genetically coded to understand the world. From the very beginning of the human ability to communicate, the way we’ve understood each other is through story. You can get a bunch of information together and try to communicate something, but you aren’t going to feel you really grasp an issue until you see it unfold in story form. The most meaningful conversations you have with your friends are you telling them stories of your experiences. People who are good at telling narratives will always be valuable.

What’s happened is that newspapers were this huge economic engine, bringing in money that was used to support all sorts of things. There was no reason a newspaper had to be the primary vehicle for narratives. Now with the financial contraction of the industry, a lot of places that were able to afford the resources, they don’t have the space. They don’t have the salaries for the best practitioners of it.

My friend David Von Drehle had this great analogy about how when he was a kid, when they needed a set of matching dinner plates, they’d buy gas at the same station over and over again. The same place, and they’d get another matching plate every time.

But just because people don’t get their dinner plates at gas stations anymore, it doesn’t mean they don’t need plates or gas. I think that could be true about narrative. Just because a lot of newspapers aren’t able to do it anymore, that doesn’t mean that people don’t need narratives, or news.

When there’s both a set of amazing facts and a manner of putting them in a narrative so that they have maximum impact, people remember these stories for decades. They don’t forget.

The question is who’s going to support the professional collection and craftsmanship required to tell these stories. I think more of this kind of thing is going directly into books. Look at all the books on the market that are talking about the financial collapse. And look at the great books on the market about the war. They’re narratives. The classic statement, “Unless you were there and saw for yourself, you can’t possibly know”—well, great narrative lets people be present at events and situations they could not actually be present for.

So books are one thing that’s going to happen. Another thing that’s going on, instead of sitting at your personal computer, more and more people are getting news on their handhelds. But when you’re talking about a handheld, they’re going to be reading maybe five sentences max. That makes the contrast all the way clear. You can’t say, “We’re satisfying their need.”

In order to satisfy a deep need, then I think there will be a lot of opportunities for niche magazines—maybe not the ones that exist now.

These new technologies are not an enemy of narrative, even if they might appear to be. You cannot stamp out that genetic coding to understand the world through narrative. It’s not going anywhere just because we’ve had a digital revolution. People who are panicking about this are taking much too narrow a view of a snapshot from a time of upheaval.

The need to understand the world through story is not going away.

What was the last narrative that knocked your socks off?

I’ve just read Finkel’s The Good Soldiers. It was devastating. I was just reading the paper and wondering, “Should we send 44,000 troops to Afghanistan?” I think we’re all guilty of this. You think of those 44,000 solders as little markers on a Risk board. But when you read Finkel’s book, you’re seeing people staring at their naked wrist, the hand blown off by an incendiary device. The guy is saying, “My hand is gone.”

Finkel makes it so you can’t think of them as markers on a Risk board anymore. These people have so little to do to protect themselves. He makes you think about it in a whole different way. It rips away that distance between war versus the reality of war.

Also, I just got through rereading—Weingarten is coming out with an anthology of his best journalism. He’s such a master storyteller. It starts with Zucchini.

That story is one of the best pieces of narrative journalism I’ve ever read.

That gets at something else about really fine narrative, which is almost mystical. I’ve already said you can’t have good writing in the absence of what it is you’re writing about. You have to have something to reveal, something to tell. Otherwise no amount of wordsmithing will save you.

We started that story with a conflict. Gene didn’t just randomly pick this guy. He heard from this friend that the Great Zucchini was coming to people’s doors at night asking for advances in cash for the party he’d be doing next Saturday.

[SPOILER ALERT!] We started with this conflict of the children’s performer with the hint of something dark there. He could have easily have reported a little and written a perfectly nice feature story without ever discovering the gambling addition or the horrible thing that happened to him as a kid with his neighbor being murdered. But because Gene reported this so deeply and was willing to spend the time talking to everyone about this guy and because his presence was so acceptable, he got to the heart of it.

Gene called me from the road and says, “I’m going to Atlantic City with him.” There was just more and more. When we started out that story, what are the odds that the guy would turn out to have all this going on? What are the odds that there was going to be this unbelievably tragic experience?

Any really great narrative journalist understands that there are no bad stories, there are only incompletely understood stories. That idea—that everything in life is going to be one hell of a story—is what drives the best. And what makes them deliver so consistently. If you look at somebody like Gene or Finkel, you might ask, “How is it that something perfect always seems to happen to them to make the story great?”

Gene and I call that the god of journalism. But the god of journalism pays off the persistent.

Is there anything narrative journalism does that can’t be done by some other type of print or online story?

Narrative journalism is not about delivering information. It’s about delivering the experience of something. That’s what other kinds of journalism, with sidebars and timelines and hypertext and graphics and mapping—all the wonderful things that journalism can do to convey information—none of those things even attempts to deliver the sense of experience. There are some exceptions to that—video, of course. But video is narrative. Also long-form Q&A’s, but those are an excuse for the person being interviewed to tell a story.

One thing I’m trying to do with my website is create an infrastructure for doing fine, nonfiction narrative. It requires time, talent and experience, and newspapers are losing the ability to provide those resources as much as they have in the past. The fact is that technology has enabled people to move it outside of newsrooms.

What stories would you like to see written that you don’t see out there today?

I’m worried about changes at the Post. I think that the Zucchini story—there’s not a place for the Post to run it, as the Post exists today. Given the requirements of the day-to-day, and the resources that have been cut, and the direction that they fell for a variety of reasons, I just don’t see those stories happening in the Post in the immediate future. There is something that’s important that’s being lost.

I understand, of course, how dire the situation is. You’re in a situation where you’re cutting a huge piece of your resources, and you have to do it. And that makes it really, really hard. But right now, I do not see a venue for a story like Zucchini to arise and develop. They’re thinking, “We don’t have the space, and we don’t have the time to spend.”

The magazine still runs stories, but they’re not as long. And they’re not going after that connection to the meaning of life that we aimed for.

You don’t know when you start doing a story like Zucchini that it’s going to wind up like it is. Of course, editors will say, “If we knew this story was out there, we’d run it. We’d find the space.” But you have to invest in it at first, when it’s just a story about a clown.

When you’re in the practice of doing deep and meaningful narrative, the success rate is remarkably high. But it’s not like you know for sure at the outset that it’s going to pay off. You have to be able to take those risks.

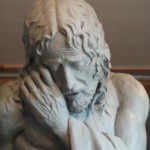

Jesus Wept

I signed on very early this morning to discover a submission in my editing inbox. The manuscript was a total of 2 words (for which a payment of $.07 was enclosed), and it came with a query: “Can you improve this.”

I signed on very early this morning to discover a submission in my editing inbox. The manuscript was a total of 2 words (for which a payment of $.07 was enclosed), and it came with a query: “Can you improve this.”

You may have guessed that the two words were: “Jesus wept.”

This is actually a famous literary trope, the assertion that the simple declarative sentence, “Jesus wept,” is one of the greatest bits of prose/poetry in the English language.

Unfortunately, it was not submitted by the author, but by one Gene Weingarten, who is the type of wiseass who, instead of calling me up to discuss this little bit of business, would, at roughly 6 a.m. when it occurred to him, go to my website, go through the whole story calculator process, pull out the credit card, and actually submit it.

No doubt he loved the idea that the total cost was 7 cents.

The more I thought about it, the more I realized that this was the essence of what Gene does. It’s a kind of performance humor, all cheeky silliness at first glance, but with a profound aftertaste.

Why is “Jesus wept” so great? Well you can find a treatise on that subject at Wikipedia.

But basically, when you can say, and imply, a tremendous amount in a very few words, it is always powerful. This is an almost perfect distilation of that phenomenon. Dealing strictly on a literary plane, there may be no more potent a figure than Jesus — both human and divine, doomed to death but destined for ressurection, a symbol of our greatest failings (as demonstrated by his persecution and crucifixion) and our only chance for salvation. And as any hack writer knows, “wept” is the go-to verb when you need to juice up the emotions fast. Put them together, and you have a nuclear explosion of meaning. Weeping is a very mortal act, uniquely human. It speaks of Jesus as a man, who can suffer in a very bodily way, pre-figuring his coming torment on the cross. If Jesus could not feel pain, his sacrifice would be meaningless. If he could not doubt, his faith would be unnecessary. The more Jesus is like the rest of us, the more power there is in his story.

So the accompanying memo with this two-word submission, a mere four words itself — “Can you improve this?” — is itself a kind of poetry. Good writing isn’t about words, it’s about meaning, and very often, the fewer words the better.

Google Only Knows

I was e-mailing a friend and a client about possible additional complications he could heap upon the hapless protagonist in his novel, and I was telling him about the time a vet charged me $150 to diagnose my dog as having a ligament tear that would require $5000 surgery followed by a three-month confinement in a crate. I ignored the diagnosis, and the dog got better on her own — something the vet had said was impossible. But that’s not the point I’m making here. The astounding thing is: seconds after I sent that e-mail, I looked to the right side of the screen in my Gmail inbox, and it was filled with ads for dog walkers, pet sitters, a veterinary instruments.

T.S. Eliot Got It Wrong

April isn’t the cruelest month. October is. The more intensely beautiful it becomes, the closer that beauty is to obliteration. On those precious few days when the sky is blue and the fall colors at a peak, the knowledge that the next windy day will blow it to hell almost makes you weep. Who needs to be reminded so vividly that nothing good can last?

April isn’t the cruelest month. October is. The more intensely beautiful it becomes, the closer that beauty is to obliteration. On those precious few days when the sky is blue and the fall colors at a peak, the knowledge that the next windy day will blow it to hell almost makes you weep. Who needs to be reminded so vividly that nothing good can last?

On the other hand, it sure is pretty.

Guest column on Achenblog

I have had a vision of the future: We all work for ourselves, answerable to no one but Google.

I came by this view after I took the buyout at The Post, where I had been editor of The Washington Post Magazine (before it became the WP magazine). But as much as I would have liked to, I couldn’t afford to retire in the sense of pursuing shuffleboard and living in pajamas. (Turned out, I could only afford the pajamas part.)

I wasn’t going to starve, but I did need some supplemental income. Originally, I had imagined that I’d pick up some new work in journalism. But despite 30 years as a newspaper writer and editor, I soon was forced to conclude that finding another newspaper job would be as likely as finding work as a stagecoach driver. Sure, there were still a few Wild West tourist traps operating, but they were downsizing to pony rides, and, in any case, none ever responded to e-mails bearing my resume.

So after a lifetime of resisting it — God, how I hate to gamble — I went all entrepreneurial on myself. I hired a guy named Steve to build a website for me, hung up an electronic, web-searchable shingle as an editor for hire and began publishing my own blog. My idea was that the thousands of people who had inundated me with manuscripts over the years may want something more from an editor than a terse rejection notice. What if they could stop that guy whose signature spelled doom in mid stroke, get him to spend some time with their writing, to tell them what they’d done wrong and how to improve?

Maybe I had the kernel of a business plan. But making it into an actual business would require an education. First I had to figure out how to buy and register a domain name for my website. I still haven’t figured out how someplace called godaddy.com has managed to acquire ownership of every site name in the universe, even those that nobody has thought of yet. But so be it. At least coming up with possible names for my editing/blogging site proved easy. I spewed dozens: writeaway.com; writenow.com, thewritestuff.com — every pun and cliché in the book. And discovered: all of them were taken.

My friend Gene Weingarten suggested tomthebutcher.com, which was both catchy and apparently available, but possibly didn’t deliver the exact message I was looking for. Whenever Gene had branded me with that name in his Post columns and chats, I told people, “I prefer Tom the Surgeon.” Which is probably why I woke up in the middle of the night and fired up my computer to type “storysurgeons” into godaddy’s search engine. Bingo. With a little application of plastic I had a website name storysurgeons.com. Five minutes later, I got an email from Google (privy to every random thought that goes through my keyboard) offering me a $100 coupon for advertising my site online. I filled out a form, and now I had an ad campaign too.

So for the cost of a week-long vacation, I had an online business and my own publishing concern. In the days that followed, I very easily slipped into writing and working the same hours I had in my Post job, except for two minor differences. One, nobody was paying me; and two, if I wanted to get up in the middle of the afternoon and take my dog for a walk in the woods, I could, and would. I found that to be a fair trade-off.

On a recent afternoon of the sort that has given fall a good name despite the fact that it is a harbinger of three months of black ice, I was stepping through a light-dappled forest, the emerging reds and golds exploding in the angled sun. A cool breeze rustled a million leaves, and I could barely hear the hum of work-day traffic beginning to build behind me. Something came over me, and I felt the urge to shout. So I did, tentatively at first, and then louder until I was screaming at the top of my lungs, “FREEDOM!” over and over like Mel Gibson in Braveheart.

Then I remembered: in the very next frames of film, Gibson has his guts slowly spooled out of his body by the executioner.

But, damn, this sense of liberation feels good. While it lasts.

Story Surgeons on Achenblog.

Tweet of the Day

Dan Snyder issues panicked report: Jim Zorn seen climbing into basket of runaway balloon.

For more inane twittering, see @tomshroder at twitter.com.

Keeping Death in Perspective

Today, as I was dealing with the fact that Weingarten is trying to write a humor column about several people he knows who have died recently, suddenly and tragically (yes, I did say a HUMOR column), I read this in the New York Times. It’s funny how irritating it is to hear 40-year-olds whining about confronting their mortality when you’re 55. But aside from that bias, is there really anything irritating about this Judith Warner column? Yes, I think. There’s a certain smugness throughout, perhaps most acutely in the following phrase:

It’s just that urgency that goes, in early middle age. All that yearning and anguish and passion had been replaced by a steady pulse of pleasure and satisfaction . . .

That blows the irritation fog horn. Primarily for blindly assuming that reaching middle age automatically comes with “a steady pulse of pleasure” — ignoring the obvious truth that her steady pulse has more to do with being an upper middle class professional with a whole lot of luck on her side than attaining the age of 40.

Anyone doing first-person writing has to be very careful about explicitly generalizing his or her own experience to everyone else, especially when wallowing in personal good fortune. Then to compound that error by COMPLAINING about one’s good fortune, as Warner does here, is really hard to forgive.

Tweet of the Day

I always dreamed of this as a child, but the reality turned into a nightmare: http://tinyurl.com/yjgpvhr

Recent Comments

- Bruce M. Gregory on Flying Tigers Take a Bite out of Amazon

- Tara Solomon on Acid Test, Optimized Edition

- Tom Shroder on My WaPo Travel Story On the Dordogne

- abriat christian on My WaPo Travel Story On the Dordogne

- Kerthy Fix on Acid Test’s Trip to the Movies

Archives

Copyright © 2024 Tom Shroder

Terms of Service & Privacy Policy | Data Access Request