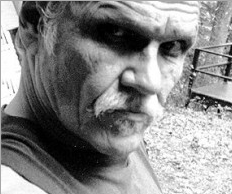

Harry Crews died yesterday. He was 76, dissipated by a lifetime of hard living, too many drugs, too much alcohol and an uncounted number of fists to the face. I couldn’t recognize the man in the obituary picture, the man described as a little-known but larger-than-life cult novelist, a writer of “dark fiction” filled with Southern grotesques and wild violence. The Harry Crews I remember was fixed in a thin slice of spacetime, a stretch of six months or so in Gainesville, Florida 40 years ago. He was in his short-lived “speed freak phase.” He’d given up drinking, at least temporarily, but he was definitely on something that turned up the wattage. He was running a lot, zero body fat, a Mr. Clean gleam, both on his shaved skull and in his eye.

Somehow I managed to get into one of his University of Florida creative writing seminars as a sophomore undergraduate. I don’t remember if I had to show a writing sample, but I imagine I must have. Crews was a writing God in 1972 Gainesville. Little-known he may be in terms of a New York Times Arts section obit in 2012, but then and there he was the most famous man in town, a swashbuckling Hemingway figure who made flesh the cliche of living legend – at least to an 18-year-old with dreams of literary fame and fortune. I do remember a one-on-one interview in which he studied me the way a hawk must study a chipmunk. He accepted maybe a dozen students that semester, a three-hour marathon one night a week which was less of a class than a performance. I have no idea why I was among them, but I have been forever grateful for that fluke of luck.

Crews spoke in great roiling torrents, extolling us like a revivalist doing his unlevel best to save a particularly sorry bunch of sinners. His gospel was the nakedness of truth, the necessity for a writer to peel away all ego, to abandon caution and conceit, and care only for revealing his inner world in all it’s sick and twisted glory. Crews, who made it quite clear he had no use for convention in life or literature, was the embodiment of Bob Dylan’s creed, “to live outside the law, you must be honest.”

There were periods in Crews’s pedagogic career when he was not the most attentive teacher. He’d show up late and half-baked to stumble and mumble around. Or fully baked, not show up at all. But in the brief moment of time when I sat at the old-fashioned wooden writing desks in an antiquated second floor classroom, a heavy scent of jasmine drifting in the open windows, he was an exemplar. Sometimes he read something he’d been working on, raw passages only ripped from his typewriter hours earlier. It was thrilling, terrifying, and disconcertingly intimate. It could have been embarrassing, but he read it with such fierce energy and conviction we were all swept up and carried away in the flood of prose, each and every one of us forever embedded with the desire to write as if we were dancing around a ring, trying to deliver a knockout punch.

That was the downside of his charisma. We weren’t so much students as disciples, and to this day, his manic rhythms throb in some recess of my brain whenever I sit at a keyboard.

Here’s the upside: One night he walked into class with an onionskin manuscript in his hands and announced that he was going to read a student piece. He set to it with the same drama and passion he’d delivered for his own work. His reading was so riveting, it wasn’t until several sentences in that I realized that he was reading my story, the story I’d suffered and strained over, and had grown to hate each and every word of.

I’m sure it wasn’t all that bad. It wasn’t all that good, either. But as Crews read it, standing and pacing before us, flailing his free arm and belting out my words as if they were fists of fury, I could see my classmates leaning forward in their seats, rapt. And for the first time, I truly believed I could become a writer.

Speak Your Mind