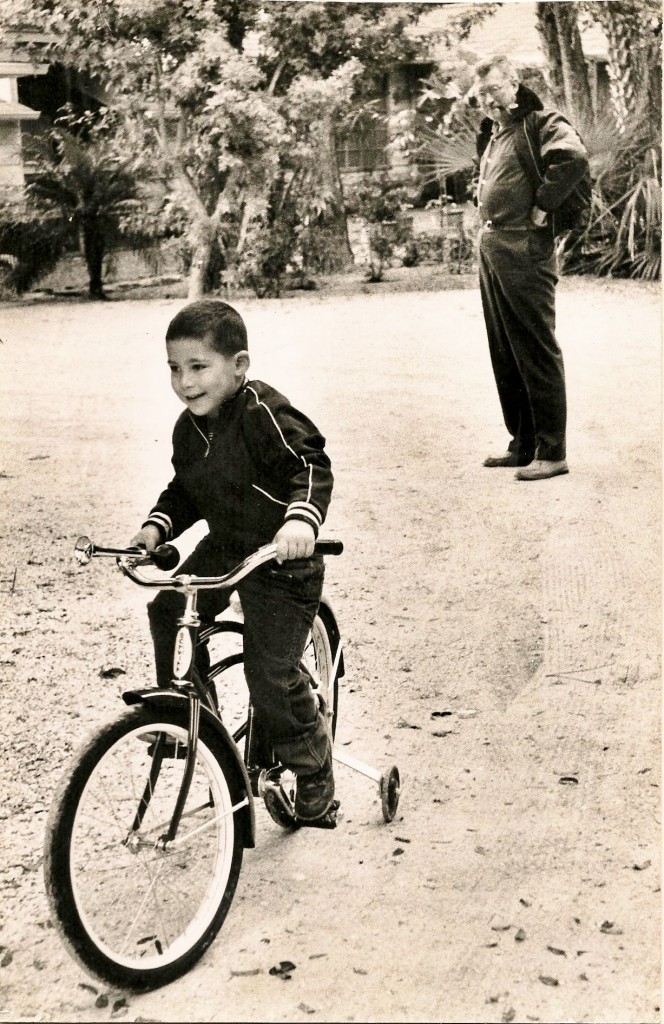

The author, age 5, watched over by the author, age 55, on his first attempt at two-wheeled conveyance, Christmas Day 1959.

Even as I continue doing talks and interviews about Acid Test, I am deep into the research phase, and close to beginning to write, a new book that is more personal and higher concept. It’s about my grandfather, the writer MacKinlay Kantor, who died almost 40 years ago. The working title is: The Most Famous Writer Who Ever Lived, an Investigative Memoir.

Irony is intended.

My mother once told me that as she and her brother, my Uncle Tim, were growing up, their father led them to believe he was the most famous writer who ever lived.

This was an absurdity, of course, but not to the degree it may at first seem. MacKinlay Kantor, wrote innumerable works of fiction and nonfiction, including 45 books, one of which, Andersonville, won the Pulitzer Prize and sat atop the bestseller lists for more than a year. Another novel, Glory for Me, was the basis for the movie “The Best Years of Our Lives,” which took seven Oscars, became the highest grossing film since “Gone with the Wind,” and is often ranked among the greatest American films of all time. These successes played out over three decades, during which Mack, as everyone called him, rose from severe starvation-level poverty to considerable wealth, appeared on popular television shows, made cameo appearances in movies. He discovered performer Burl Ives, mentored crime novelist John D. MacDonald and hung out with the likes of Grant Wood, Sherwood Anderson, Stephen Vincent Benet and Ernest Hemingway.

Despite this undeniably impressive resume, my siblings and I tended to discount our grandfather’s claim to fame as overblown and considered him more pompous than legitimately famous. By the time he died, when I was in my early 20s, his work had largely faded in the public mind. Though my mother and my uncle kept trying to push the significance of their father’s biography on us, we rolled our eyes and mostly ignored them – glanced at the old newspaper clippings without reading, thought about what we were going to do after dinner rather than listen to yet another story from the distant past. Though his many books lined a shelf in my bookcase, I never so much as attempted to read them – save for Andersonville, which I attempted twice, and both times failed to penetrate beyond page 30. For us, as with so many people, maybe even most, even extreme dramas in family history beyond one generation removed become a kind of white noise, tuned out until it’s too late.

Now my mother and uncle are both dead, as is everyone else who knew my grandfather intimately. I can’t explain why it never occurred to me that my deciding, at age 12, that I wanted to become a writer, or the fact that I actually succeeded in that rather ludicrous ambition, might have something to do with my heritage. Again, like so many people, I never considered that I might have been formed or even influenced by the abilities, proclivities or eccentricities of my near and distant forbears until the main sources of knowledge about them had vanished from the face of the earth.

Who arrives at maturity without experiencing that regret? Suddenly, questions about the past, your past and your family’s past, begin to flood in, questions that could have been so easily and profitably answered during the lifetimes of your parents or their parents, but now are literally unanswerable, lost forever behind the impenetrable veil of death.

But I had an advantage, if not unique, at least exceedingly rare: In the Library of Congress of the Unites States, less than 25 miles from my home, is a room filled with boxes of indexed correspondence, contracts, manuscripts, photographs, journals, paraphernalia and even an unpublished autobiography once belonging to my grandfather, not to mention the 45 books that were published, including two published autobiographies, as well as a published memoir by my uncle – none of which I had ever read.

Beginning with this mountain of evidence, I am discovering as much as I possibly can about the man MacKinlay Kantor, and other of my ancestors as they seem to become relevant, and to ponder the significance of my discoveries in my own life. The process of researching and writing the book will be the journey of discovery, not only into the specifics of my own family and how they relate to me, but to the significance of ancestry in general.

I will explore the anthropology, science and history of interest in family lineage, from the origins and history of kinship itself to the practice of ancestor worship to the common fact that in preliterate cultures people memorized lineage going back a dozen generations to the drive of adopted children to find birth parents to the study of how personality traits relate to inherited DNAto modern studies indicating that people who know more about their ancestral roots tend to be happier and more successful – and to everything in between. In both personal and scientific terms, I will attempt to plumb the depths and find the bottom of the mystery of why where we literally came from — biologically, genetically, emotionally – retains such a hold on us as individuals and society as a whole.

And in the end, it will be an investigation into what can be recovered and what is irretrievably lost; what can be made sense of and what will remain forever unclear.

The Most Famous Writer Who Ever Lived will, as the title suggests, also be a study of the art of writing, written by someone who is a fourth generation professional writer, someone who, until now, had been unable to read the work of his own grandfather – a certifiable piece of the American literary canon. What was it about the writing that put me off? What part of it seems to echo in my own work? What does it say about changing literary tastes, and how does it prefigure the inevitable, if not already hastening, obsolescence of what I consider to be fine writing?

In the end, it will be a meditation on how we all have dual and conflicting tendencies, resisting our genealogical past as if it were an existential threat, yet ultimately pining to connect with it, even as it vanishes before our eyes.

Having been subjected to (entertained by) many of Mack’s, what seemed like endless stories told at Prim Rose Path, I can’t wait to read, at least the first 30 pages, (LOL) of your book.

You da man Sweeny. You delivered a key moment. I’ll send you a book when it comes out next fall.

Fascinating, Tom, I look forward to the release. And btw, I read Andersonville because of our friendship and the fact that I had met Mack but I don’t remember much about it. Not sure if this is worse than not reading…

Reading it is quite the accomplishment! That sucker is long.