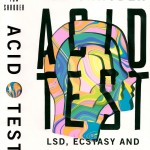

The Library Journal review of Acid Test has surfaced. My name’s misspelled (even though it’s right there big on the book cover beside the review), but they call me a “distinguished journalist/author” so they get a pass. (Scroll down until you see that psychedelic cover.)

Author & Editor

News

All Acid Test Reviews Now On Amazon

After months of trying and failing, ALL the reviews and endorsements for Acid Test are up on the Amazon page. Initially, a company representative said we were limited to five 250-word reviews, period. Fine, except look on Amazon. Books have dozens of them all the time. Sure enough, that didn’t turn out to be the case. Anyway, here they are:

– Booklist, STARRED REVIEW

“A well-respected journalist offers evidence, both empirical and anecdotal, about the therapeutic benefits of psychedelic drugs… this clear-eyed account [explores] both the complex history of the issue and the current thinking on the use of LSD, Ecstasy and other psychotropic substances for healing troubled minds… Occasionally, the stories are amusing… often, they’re moving… a perceptive criticism of the failings of America’s war on drugs, and Shroder delivers an important historical perspective on a highly controversial issue in modern medicine.” – Kirkus

“[Acid Test] explores the therapeutic possibilities of LSD and Ecstasy (MDMA), and, more broadly, the potential of the human mind… Guided by Shroder’s easy narrative tone, readers follow an activist, a marine, and a physician-turned-psychiatrist who developed a philosophy of psychedelic therapy through self-experimentation… Shroder both informs readers about the drugs’ shadowy pasts and provides insight into the future of mental health.” – Publishers Weekly

“This is not about the 60’s. This book reveals the ongoing struggle to create valuable lasting therapies for PTSD in all its forms. Funny, hopeful, and sad by turns, these stories make me believe that someday soon, MDMA will be accepted as valuable, even desirable, to counteract the despair of so many returning veterans and other souls whose lives are turned upside down by PTSD. If ever interventions are needed, it is now. Acid Test presents an alternative to anguish and anxiety, showing a route of return to balance by use of compassionate therapies along with an outlaw drug. Millions of Americans suffer from the terrors of war or crime , and perhaps soon, we can say help is on the way.”

– Carolyn Garcia, also known as Mountain Girl, a former Merry prankster and wife of Jerry Garcia

“Over the last thirty years women have gone from the kitchen to the boardroom, people of color from the woodshed to the White House, gay men and women from the closet to the altar, and all of us have embraced a new vision of life itself on this fragile blue planet. Yet when we recall the factors that unleashed these dramatic transformations there is one ingredient in the recipe of social change that is always expunged from the record: the fact that millions of us lay prostrate before the gates of awe having ingested LSD or some other psychedelic. Tom Shroder’s Acid Test is an inspiring and profoundly hopeful book.”

– Wade Davis, author of The Serpent and the Rainbow

“Tom Shroder has written a book that is at once captivating and utterly surprising, with mind-blowing revelations of a lost history. The scourge of war and trauma and the mysteries of human consciousness fills virtually every one of the gripping chapters. With its impressive research, masterful storytelling and ultimately, the possibility of hope and healing, Acid Test is destined to be an important book.”

– Brigid Schulte, author of Overwhelmed

“Acid Test is a trip of a different kind. Tom Shroder makes the hunt for relief from modern wars’ biggest killers – depression and post-traumatic stress disorder-come alive in bright, unforgettable colors, characters and emotions.”

– Dana Priest, Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter and author of Top Secret America

“Acid Test is a breath of fresh air after half a century of general hysteria, misinformation, confusion and questionable decisions of scientific, political, and legal authorities concerning psychedelic substances. Tom Shroder’s fascinating, well – researched, and clearly written account of psychedelic history, from the discovery of LSD to the current worldwide renaissance of interest in these remarkable substances and revival of research in this area, is a tour de force. Most important—socially, economically, and politically – is the book’s focus on the psychedelic newcomer MDMA (Ecstasy). The pilot studies of this substance suggest that it might play an important role in helping to solve the formidable problem of PTSD that kills more American soldiers than the weapons of enemies.”

– Stanislav Grof, M.D., author of LSD Psychotherapy, The Ultimate Journey, and Psychology of the Future

“I read Acid Test with wonder and excitement. Wonder at seeing a controversial topic through Tom Shroder’s fresh and lucid eyes. And excitement at the promise of healing that he reveals.”

– David Von Drehle, author of Rise to Greatness: Abraham Lincoln and America’s Most Perilous Year

“Tom Shroder weaves together three compelling stories with such mastery that Acid Test reads like a first-rate novel. The book is that much more intriguing and consequential though because the stories are true and the subject matter – the healing of post – traumatic stress – of great currency and importance. We need to know how to treat the trauma that afflicts most of the world or we’re in deep trouble.”

– Richard Rockefeller, former chairman of U.S. Advisory Board of Doctors Without Borders

“If you think LSD is a relic of the Sixties, or good for nothing except getting high, you need to read this riveting and important book. It’s the fascinating story of how LSD and MDMA can, with controlled use, bring near-miraculous benefits to people suffering from mental trauma. Tom Shroder is a fine journalist and a terrific writer; in Acid Test, he’s written a book that should start a long-overdue national conversation, and someday may help to end a lot of unnecessary suffering.”

– Dave Barry

“A captivating narrative with irresistible characters. It will leave you wondering whether we have the moral right to oppose this breakthrough therapy.”

– Gene Weingarten, two-time Pulitzer Prize winning author of The Fiddler in the Subway

“Acid Test is a superb book. The people Tom Shroder introduces us to are across-the-board fascinating, the reporting he’s done is deep and persuasive, and the writing is dazzling. Best of all, though, is what any open-minded reader will feel after finishing Acid Test: In a world of hurt, here is a new version of hope.”

– David Finkel, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Good Soldiers and Thank You for Your Service

“Acid Test is a trip of a different kind. Tom Shroder makes the hunt for relief from modern wars’ biggest killers – depression and post-traumatic stress disorder – come alive in bright, unforgettable colors, characters and emotions.”

– Dana Priest, Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter and author of Top Secret America

“Acid Test represents such a critical contribution to our societal awareness, one that I am honored to wholeheartedly support. Faced with the challenge to alleviate the suffering of today’s combat veterans, we must open ourselves to considering new modalities, revisiting therapeutic agents criminalized by fear and ideology, and harnessing the power of healing rituals and ancient wisdom. Tom Shroder offers a timely and compelling story of stories, illustrating the struggles and opportunities for hope and healing. Put politics and preconceptions aside; open your mind; read this book; follow the data; and speak truth to power so that scientific rigor and emerging knowledge can lead the way. We owe our fellow humans no less.”

– Loree Sutton, psychiatrist, retired US Army Brigadier General and founding director of the Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury

Facebook Acid Test Page

I’ll be keeping a pre- and post-publication blog on Acid Test on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/AcidTestbook.

Why Acid Test?

A word on the title: Yes, Acid Test was what Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters called the famous LSD bacchanals they sponsored in the Bay Area in the 1960s, and, yes, Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test is the famous and I bet still fun to read book about Kesey and the Pranksters by Tom Wolfe, and yes Acid refers to LSD when much of my Acid Test is about MDMA. So why use Acid Test as the main title? Multiple reasons. First, modern scientific and medical interest in psychedelics as a tool for psychiatric healing clearly began with the accidental discovery of the cognitive effects of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide. Second, the the term “acid test” originally referred to a process in which strong acid is used to distinguish gold from base metals. Used in the context of early LSD use, it was meant to imply that in these circumstances the drug could reveal some profound truth. In the context of my book, it suggests the long, absurdly uphill process by which researchers have attempted to determine/prove whether psychedelic therapy is psychiatric gold or toxic lead.

A word on the title: Yes, Acid Test was what Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters called the famous LSD bacchanals they sponsored in the Bay Area in the 1960s, and, yes, Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test is the famous and I bet still fun to read book about Kesey and the Pranksters by Tom Wolfe, and yes Acid refers to LSD when much of my Acid Test is about MDMA. So why use Acid Test as the main title? Multiple reasons. First, modern scientific and medical interest in psychedelics as a tool for psychiatric healing clearly began with the accidental discovery of the cognitive effects of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide. Second, the the term “acid test” originally referred to a process in which strong acid is used to distinguish gold from base metals. Used in the context of early LSD use, it was meant to imply that in these circumstances the drug could reveal some profound truth. In the context of my book, it suggests the long, absurdly uphill process by which researchers have attempted to determine/prove whether psychedelic therapy is psychiatric gold or toxic lead.

Excerpt from Acid Test: LSD, Ecstasy and the Power to Heal:

One of the many who got his hands on a hit of the Sandoz-manufactured LSD, floating free from all the loosely audited experimental trials, was a 30-year-old eccentric, the grandson of a U.S.senator, named Owsley Stanley. His acid experience impressed him as the key to a new, more profound and caring cosmos, and launched Stanley on an historic quest. He hooked up with a Berkeley chem major named Melissa Cargill, and in three weeks at the university library in Berkeley, they taught themselves how to manufacture fantastically pure LSD, which he loosed upon the streets of a growing bohemian enclave in San Francisco’s Haight Ashbury. Those 3,600 colored capsules passed hand to hand in the spring of 1965 were the first of millions of acid trips he would be directly responsible for.

“I never set out to ‘turn on the world,’ as has been claimed by many,” Owsley told Rolling Stone magazine in a 2007 profile, four years before he died in a car crash. “I just wanted to know the dose and purity of what I took into my own body. Almost before I realized what was happening, the whole affair had gotten completely out of hand. I was riding a magic stallion. A Pegasus.”

One of Owsley’s earliest and most consequential clients was Ken Kesey, who needed a new source of inspiration now that he was no longer picking up spare change and free acid as a guinea pig in the CIA-funded LSD trials in Menlo Park. Unlike the first wave of acid acolytes, Kesey wasn’t an academy-educated intellectual or professional behaviorist. He was a salt of the earth, and he didn’t want to study LSD, he wanted to ride it like a wave. He just happened to bring the rest of the culture with him. Fueled by Owsley product, Kesey and a growing group of rabble-rousing fellow travelers began staging outrageous bacchanal’s called acid tests – a play on the confluence of the drug’s new street name with a process in which strong acid is used to distinguish gold from base metals. The term was meant to imply that the use of LSD in these circumstances could reveal some ultimate truth. Actually, Kesey’s parties mostly revealed what happened when large numbers of random strangers consumed immoderate amounts of psychedelic in wildly uncontrolled circumstances as a tsunami of sound rolled over them from the tolling guitars of the Grateful Dead.

Just as the Kesey-Owsley confederation was electrifying the West Coast, a Harvard professor named Timothy Leary was doing his best to light up the East. Leary, who had begun as just one of the scores of academics studying the fascinating effects of the new drug in clinical trials, became his own best (or worst, depending on perspective) subject. Harvard grew impatient with Leary and his partner in the psychedelic experimentation, another Harvard professor, Richard Alpert, when it got around that the pair had been handing out informal homework to students, in the form of psychoactive chemicals. When both men were eventually dismissed — Alpert for defying an order to surrender his entire psilocybin stash to the university for safe keeping, and Leary for going AWOL from his teaching assignments — a front page editorial in the student-run Harvard Crimson applauded: “Harvard has disassociated itself not only from flagrant dishonesty but also from behavior that is spreading infection throughout the academic community.”

Fine with Leary. He’d concluded from his acid trips that the rules and limitations of conventional society were false fronts, head games designed to control and manipulate. He began to advocate a juiced-up liberation theology based on the psychedelic experience, and he learned to enjoy getting under the skin of the unenlightened. For an academic, he had a surprising knack for attracting attention.

In a 1966 Playboy interview he delivered this gem:

“An enormous amount of energy from every fiber of your body is released under LSD most especially including sexual energy. There is no question that LSD is the most powerful aphrodisiac ever discovered by man. Compared with sex under LSD, the way you’ve been making love, no matter how ecstatic the pleasure you think you get from it, is like making love to a department-store-window dummy.”

Between Leary’s hype, Kesey’s beat charm and Owsley’s prowess in the laboratory, psychedelics went viral, creating a drug subculture in which millions of unscreened Americans experimented with drugs of uncertain purity produced by less talented chemists than Owsley.

Hard Love

I now read two-thirds of the books I read using an e-reader app on my phone. I can hold it and flip pages using one hand and carry an entire library in my pocket, which I can pull out at the drop of a long stop light. But I have to say, when my editor sent me this photo of the proof copy of the hardcover of Acid Test, it was love at first sight. In the end, the romance of this folded envelope of fabric-covered board and the stiffly bound sheaf of high quality paper within is enough to make the spirit soar. And note the monogram!

A Terrible Tragedy

Richard Rockefeller wasn’t just a famous name, he was a wonderful man, a physician who devoted himself to victims of the world’s many traumas and for 21 years was chairman of the United States Advisory Board of Doctors Without Borders. I got to know Richard personally while reporting my book Acid Test. Just last week he wrote me a wonderful blurb for the book jacket, kind, thoughtful and generous. Richard was a tireless supporter of the promising clinical research which is proving that MDMA assisted therapy is of potentially tremendous benefit to people with trauma-induced psychological disorders for whom conventional therapy has been woefully inadequate. This morning, Friday the 13th, Richard took off in his small plane from an airport in New York. Something went wrong. The plane never reached cruising altitude and almost immediately went down. He was the only one in the plane, and died on impact. There was so much he was looking forward to now that responsible investigations of the use of psychedelic drugs in therapy were beginning to win acceptance in mainstream culture. He’d already done so much to make that happen. His loss is great, but what he contributed to the world should not be forgotten.

Publisher Weekly’s Review of Acid Test

Kirkus Reviews Acid Test

The first pre-publication review of Acid Test:

ACID TEST

LSD, Ecstasy, and the Power to Heal

Author: Tom Shroder

Review Issue Date: July 1, 2014

Online Publish Date: June 11, 2014

Publisher:Blue Rider Press

Pages: 448

Price ( Hardcover ): $27.95

Publication Date: September 9, 2014

ISBN ( Hardcover ): 978-0-399-16279-4

Category: Nonfiction

A well-respected journalist offers evidence, both empirical and anecdotal, about the therapeutic benefits of psychedelic drugs.

The late comedian Bill Hicks, prone to taking what psychedelic bard Terence McKenna called “heroic doses” of mushrooms, used to refer to the use of drugs as “squeegeeing open your third eye.” In this cleareyed account, former Washington Post Magazine editor Shroder (Old Souls: The Scientific Evidence For Past Lives, 1999, etc.) explores both the complex history of the issue and the current thinking on the use of LSD, Ecstasy and other psychotropic substances for healing troubled minds. Thankfully, the author only briefly touches on the usual tropes—there’s a thoughtful chapter on Aldous Huxley’s introduction to LSD, after which he wrote, “To fathom Hell or soar angelic, Just take a pinch of psychedelic,”—but Shroder skims over old stories about Ken Kesey, Owsley Stanley and Timothy Leary that have plagued authentic researchers for years. Instead, the author tells his complex story via three men: Rick Doblin, the founder of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies; Michael Mithoefer, a former emergency room doctor whose interest in exploring his own mind led him to become a trauma psychologist; and Nick Blackston, a U.S. Marine whose war experiences are characteristic of the waves of soldiers returning from war with catastrophic PTSD. Occasionally, the stories are amusing: At one point, Doblin was being considered for an internship at the Food and Drug Administration. Upon being turned down, he thought, “Now I can still smoke pot and don’t have to wear a suit.” More often, they’re moving—e.g., Mithoefer’s assistance with a variety of patients, many of whom spoke on the record about their experiences, to discover what the doctor calls “inner healing intelligence.” Add to these stories a perceptive criticism of the failings of America’s war on drugs, and Shroder delivers an important historical perspective on a highly controversial issue in modern medicine.

An observant argument for understanding a society through the drugs it uses.

Northern Virginia Magazine Profile Piece Online

The writer, Helen Mondloch’s, day job is teaching kids English. You can see the English teacher in how much of my stuff she read, and how carefully, before interviewing me. I really appreciated that. You can find the article here.

Reverse POV

Last year I got a call from a journalist in New Zealand named Charles Anderson who wanted to do something radical: pay me out of his own pocket to edit a multimedia feature he was doing for Fairfax Media on the search for a plane that had been lost for 85 years a la Amelia Earhart. Charles just emailed me to let me know the resulting piece, a glorious use of digital technology to tell a story in multiple dimensions, has just won a big national award for journalistic innovation. But what I found most interesting was a link he sent of an interview he gave describing the process of working with me — a rare glimpse from the other side of an editing project:

Last year I got a call from a journalist in New Zealand named Charles Anderson who wanted to do something radical: pay me out of his own pocket to edit a multimedia feature he was doing for Fairfax Media on the search for a plane that had been lost for 85 years a la Amelia Earhart. Charles just emailed me to let me know the resulting piece, a glorious use of digital technology to tell a story in multiple dimensions, has just won a big national award for journalistic innovation. But what I found most interesting was a link he sent of an interview he gave describing the process of working with me — a rare glimpse from the other side of an editing project:

When I was working on it, this guy Tom Shroder, who’d edited Gene Weingarten – a Washington Post writer who’d won two Pulitzers – I saw he’d been made redundant and was a gun for hire editing whatever. I thought it would be great to have someone of that calibre edit your work. He said sure. I did it out of my own pocket, but you get to a stage where if you want to be better at something then you want someone to be pretty critical and somebody who’s got experience like that is pretty invaluable.

That was a really interesting editing process, because I had about 6000 words in the final draft to him, and we had about eight back-and-forths and he would just go through the whole thing and have screeds of notes and questions. Everything had to be explained and qualified and it made me realise that the reader isn’t stupid, but they do need to be led along a path and everything has to be easy to understand. It’s a lot easier to read if it’s just effortless because everything makes perfect sense in their minds.

The final draft was 8000 words, so editing wasn’t necessarily cutting down; it was making it more intelligible and readable.

It was nice when it came out, because you want to promote it, and being able to say he edited it gave it some credence in the States. It wasn’t just some hack at the bottom of the world.

Read the piece: Charles Anderson is no hack.

Recent Comments

- Billy Hughes on Tom Shroder, Guru

- Jeff Gill on The “Misattribution of Meaning” (Or Not)

- Bruce M. Gregory on Flying Tigers Take a Bite out of Amazon

- Tara Solomon on Acid Test, Optimized Edition

- Tom Shroder on My WaPo Travel Story On the Dordogne

Archives

Copyright © 2025 Tom Shroder

Terms of Service & Privacy Policy | Data Access Request