People ask me, Tom, what’s your proudest accomplishment? Turn’s out,

that’s an easy question to answer. It’s not any journalism prizes, book

titles, or even paternity

It’s having an indie rock song named after me. A DC group called the Gena Rowlands Band, led by a guy named Bob Massey who was once a news aide at the Washington Post, wrote a song that seems to be about someone waking up in someone else’s body — which was either inspired by or made Bob think of Old Souls, my book on cases of small children who appear to recall previous lives. It’s called Tom Shroder’s Blues, a tribute no doubt to the immortal 1976 Tom Waits ballad, Tom Traubert’s Blues (which may be my favorite Waits tune of all, and his best lyrics).*

Actually, the Gena Rowlands Band isn’t bad at all. You can hear some of their work on YouTube, though unfortunately not Tom Shroder’s Blues, (only 99 cents at the i-Tunes Store!) Not that I’m shilling for it. I don’t get a cut. Though maybe I should.

*Tom Traubert’s Blues

Wasted and wounded, it ain’t what the moon did

Got what I paid for now

See ya tomorrow, hey Frank can I borrow

A couple of bucks from you?

To go waltzing Matilda, waltzing Matilda

You’ll go a waltzing Matilda with me

I’m an innocent victim of a blinded alley

And tired of all these soldiers here

No one speaks English and everything’s broken

And my Stacys are soaking wet

To go waltzing Matilda, waltzing Matilda

You’ll go a waltzing Matilda with me

Now the dogs are barking and the taxi cab’s parking

A lot they can do for me

I begged you to stab me, you tore my shirt open

And I’m down on my knees tonight

Old Bushmill’s I staggered, you buried the dagger

Your silhouette window light

To go waltzing Matilda, waltzing Matilda

You’ll go a waltzing Matilda with me

Now I lost my Saint Christopher now that I’ve kissed her

And the one-armed bandit knows

And the maverick Chinaman and the cold-blooded signs

And the girls down by the strip-tease shows

Go, waltzing Matilda, waltzing Matilda

You’ll go a waltzing Matilda with me

No, I don’t want your sympathy

The fugitives say that the streets aren’t for dreaming now

Manslaughter dragnets and the ghosts that sell memories

They want a piece of the action anyhow

Go, waltzing Matilda, waltzing Matilda

You’ll go a waltzing Matilda with me

And you can ask any sailor and the keys from the jailor

And the old men in wheelchairs know

That Matilda’s the defendant, she killed about a hundred

And she follows wherever you may go

Waltzing Matilda, waltzing Matilda

You’ll go a waltzing Matilda with me

And it’s a battered old suitcase to a hotel someplace

And a wound that will never heal

No prima donna, the perfume is on

An old shirt that is stained with blood and whiskey

And goodnight to the street sweepers

The night watchman flame keepers and goodnight to Matilda too

For those who have a vested interest in decently compensated professional journalism, a sentimental fondness for it, or a core belief that what it contributes to democracy is essential, a recent

For those who have a vested interest in decently compensated professional journalism, a sentimental fondness for it, or a core belief that what it contributes to democracy is essential, a recent

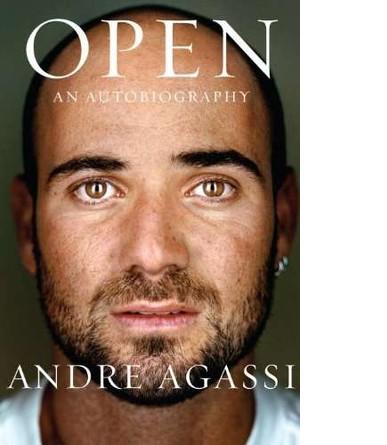

So I loved the book, admired the heck out of the craft. But there were two things I would have pushed if I were editing it. One of the central themes of the book, demonstrated beautifully, was that in spite of being one of the best in the world, Agassi HATED tennis. Really hated it. If I were Moehringer, I would have pushed him harder on that: Clearly he hated the pressure of expectations. He hated the toll it took on his body. He hated the loneliness and isolation, the endless repetition and the way it consumed his life. But did he hate the way it felt when his body executed a virtuoso maneuver, when he was able to leap from the court, swing perfectly, meet the ball at the sweetest possible spot and drive it over 100 miles per hour to the exact square inch of the court he’d chosen? When he was able to do that over and over again? Did he hate the challenge of the intricate chess match? The way tennis forces you to live in the moment, experience the primal fullness of battle without severed limbs and rotting corpses?

So I loved the book, admired the heck out of the craft. But there were two things I would have pushed if I were editing it. One of the central themes of the book, demonstrated beautifully, was that in spite of being one of the best in the world, Agassi HATED tennis. Really hated it. If I were Moehringer, I would have pushed him harder on that: Clearly he hated the pressure of expectations. He hated the toll it took on his body. He hated the loneliness and isolation, the endless repetition and the way it consumed his life. But did he hate the way it felt when his body executed a virtuoso maneuver, when he was able to leap from the court, swing perfectly, meet the ball at the sweetest possible spot and drive it over 100 miles per hour to the exact square inch of the court he’d chosen? When he was able to do that over and over again? Did he hate the challenge of the intricate chess match? The way tennis forces you to live in the moment, experience the primal fullness of battle without severed limbs and rotting corpses? clude huge laundry lists of events and facts about a life just because, well, it’s a biography. Open includes plenty of facts that might have been groaningly boring, down to the minutiae of long ago and long forgotten sequences of strokes on an obscure tennis court somewhere. But every single one of them is included only if it makes a point in the larger argument of the story.

clude huge laundry lists of events and facts about a life just because, well, it’s a biography. Open includes plenty of facts that might have been groaningly boring, down to the minutiae of long ago and long forgotten sequences of strokes on an obscure tennis court somewhere. But every single one of them is included only if it makes a point in the larger argument of the story. I had this great encounter with Pete, the uber-personal trainer at the Y. He’s a guy you might take for a stereotypical jock. He’s normally all about new ways to stress your core, but the other day he’d just read a book — a BOOK! — that had bowled him over, and he couldn’t stop talking about it. It was like someone newly (and gaggingly) in love who can’t stop going on about his beloved. And they say narrative is dead. Before we write the obit, we’ve got to account for Pete.

I had this great encounter with Pete, the uber-personal trainer at the Y. He’s a guy you might take for a stereotypical jock. He’s normally all about new ways to stress your core, but the other day he’d just read a book — a BOOK! — that had bowled him over, and he couldn’t stop talking about it. It was like someone newly (and gaggingly) in love who can’t stop going on about his beloved. And they say narrative is dead. Before we write the obit, we’ve got to account for Pete.