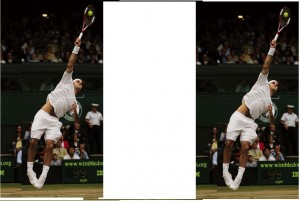

I wrote an article a couple months shy of three years ago about a couple of DC-area teenagers who were trying to make it on the junior tennis circuit, and had dreams of making it in the pros. In the article, titled Net Gain, I made it clear that even though they were among the top juniors in the world, their chances of actually succeeding as pros, defined roughly as a handful of years among the top-100 players in the world, were exceedingly small.

The other night, I had the thrill of watching one of the two, Denis Kudla, play Roger Federer in front of thousands packing a stadium in the second round of the prestigious Indian Wells CA tournament. Kudla, now 19, was facing off against possibly the greatest player in the game’s history at one of his hottest moments in years. Federer would go on to win the tournament, and Kudla had never been past the first round in a tournament of this magnitude, had never faced a top-10 player, and had never played before so many fans on international television. He looked appropriately nervous, like a man who suddenly was aware of every nerve signal and muscle twitch it took to simply stand up and walk to his end of the court, much less return a 130 mph snaking serve that dips on the line as if it had telemetry.

Yet, incredibly, despite a very tight-armed double-fault, Kudla held his first serve, and even aced Fed down the T.

He went on to lose of course, 6-4, 6-1, but not before breaking Federer once in the first set, and having a break chance in the second. His second-round finish was enough to move him up further in his steady climb through the rankings. He’s now at 175 in the world, and he’s in the top 10 of all American pros.

The other star of my article, a kid I watched grow up at my racket club in Fairfax VA, was Mitchell Frank. Frank parted ways with Kudla at the end of his junior career and, instead of trying to go pro, accepted a scholarship to the University of Virginia, where he instantly became the No 1 ranked college player in the country. It used to be fair to say that players who went the college route, and stayed there for the full four-years, rarely amounted to anything in the pros.

But a guy named John Isner, who went to the University of Georgia and graduated there, is now the No 10 player in the world. It was Isner who faced Federer in the finals of the Indian Wells tournament. He lost, too. But still.